|

|

|

And speaking of things that haunt you from old New Yorkers, there is this:

“Be regular and orderly in your life, so that you may be violent and original in your work.”

*

Also. How this:

Hiding in plain sight is how she tries to negotiate her public life. “I try to make myself small,” she told me. “I try not to call attention to myself.” The novelist Michael Cunningham remembers going out for a coffee with Moore, who had starred in the 2002 Stephen Daldry movie based on his novel “The Hours.” As they stepped outside, he noticed that she changed. “You just did something, didn’t you?” he asked. “She said, ‘No.’ I said, ‘You retracted your beauty, didn’t you?’ She said, ‘Oh, yeah, kind of,’” Cunningham said. “She pulled something in. There was a glow that she’d emanated in the living room that she could retract in the street.”

Reminds you of this:

Jude looked at him. “Only you could be on magazine covers and not think you're famous,” he said, fondly. But Willem wasn't anywhere real when those magazine covers came out; he was on set. On set, everyone acted like they were famous.

“It's different,” he told Jude. “I can't explain it.” But later, in the car to the airport, he realized what the difference was. Yes, he was used to being looked at. [...] Perversely, though, as this was happening more and more—he would enter a room, a restaurant, a building, and would feel, just for a second, a slight collective pause—he also began realizing that he could turn his own visibility on and off. If he walked into a restaurant expecting to be recognized, he always was. And if he walked in expecting not to be, he rarely was. He was never able to determine what, exactly, beyond his simply willing it, made the difference. But it worked; it was why, six years after that lunch, he was able to walk through much of SoHo in plain sight, more or less, after he moved in with Jude.

(The way, maybe, the first cappuccino you have after you return to Italy, reminds you of the last cappuccino you had anywhere else.)

[nightingaleshiraz] [?]

[Santo Spirito, Firenze]

[mercoledì 15 novembre 2017 ore 11:26:26] [¶]

|

|

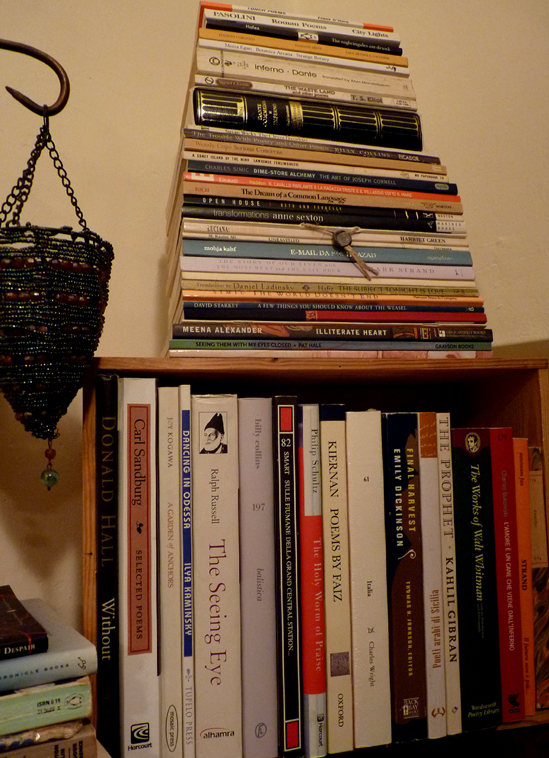

For a long time, I’d been wanting, trying, to find and re-read an essay I'd read in a New Yorker from years and years ago. Something about libraries and what they say about our selves.

I started by searching the New Yorker website for every article that has the words “personal” and “library” in it (though not necessarily together). Zilch. I thought harder, and remembered something about a big house. So I searched the New Yorker website for every article that had the words “library” and “mansion” in it (though not necessarily together). Nada. I knew I'd read it in print and not online, so I searched in “magazine content” only. I searched from my laptop, from my tablet, on different days in case different days would make a difference. Finally, today, I gave up on the New Yorker website entirely, and simply asked Google to find me things that have to do with the phrase “new yorker” (with the quotes) and the words “what our libraries say about our selves” (without the quotes). It came up immediately — second in the search results. I feel like there's a lesson in there. If not for me, then maybe for whoever is writing code for the New Yorker.

Anyway. It was worth it, to reconsider all the things he has one consider.

Like how a long shelf of careful, brilliant books, all devoted to one subject, was the best possible life that subject could enjoy.

Or how the acquisition of a book signalled not just the potential acquisition of knowledge but also something like the property rights to a piece of ground: the knowledge became a visitable place.

Also, how our own libraries can be paradoxical: they are as personal as the collector, and at the same time are an ideal statement of knowledge that is impersonal, because it is universal, abstract, and so much larger than an individual life.

And how too, there is the paradox of permanence (though I might call it more of a paradox of something else — something to do with representation, or significance, or space): a single photograph of a book-filled room might be more redolent of its owner than the books themselves.

And finally, especially, how in any private library the totality of books is meaningful, while each individual volume is relatively meaningless. Or, rather, once separated from its family, each individual book becomes relatively meaningless in relation to the original collector, but suddenly newly meaningful as the totality of the author’s mind. The lovely book “Mecca: A Literary History of the Muslim Holy Land,” by the great New York University scholar F. E. Peters, says nothing about my father-in-law, except that he bought it (and, to judge by its pristinity, only bought it); but it represents a distillation of Professor Peters’s lifework. In this strange way, our libraries are like certain paintings that, as you get closer to the canvas, become separate and unreadable blobs and daubs of paint.

That was the part that struck me most all those years ago; that was what I most wanted to have at hand again. This idea of one's library as something like a mosaic: each piece contributes to making the picture, but only because every other piece does too.

What I didn’t remember at all, is that it was an essay by James Wood. James Wood in 2011. It strikes me now that this was before I started the master's, and therefore before I more fully understood how much I liked many things by James Wood.

It strikes me too, that the week it was published, the issue it was in, was exactly seven years ago this week.

I think of itches, hills, sins and habits. The ages of man and the stages of grief. The number of years between Abba and Amma. I think about where and who I was, exactly seven years ago this week.

I think of whether seven Novembers from now, I will still be here in this house. Books and shelves and all.

[nightingaleshiraz] [?]

[Santo Spirito, Firenze]

[lunedì 06 novembre 2017 ore 10:47:11] [¶]

|

|

|